The letters and diary of A.P Derham, stored in the University of Melbourne archives, reveal a steadfast young medical student who served in both WW1 and WW2.

The story of Alfred Plumley Derham is one of a young medical student who showed great steadfastness in the face of the day-to-day realities of WWI: boredom, tough living conditions, separation from loved ones, crippling injury and illness. The letters and diaries of A.P. Derham include both detailed description and poetic reflection, and give great insight into the experience of war and landing at Gallipoli. They also feature personal moments, including his engagement to Frances “Frankie” Anderson while on active service.

Derham was a fourth year medical student when WWI broke out in August 1914 and suspended his studies with the hope of enlisting i. In a letter to Frances, he told her that on enquiring about joining the Army Medical Corps of the 5th Australian Infantry Division he was told that it was “full up and 4 men over”. Derham persisted, and recalled that “by smiling sweetly however I managed to persuade them I was an invaluable addition.”ii In a letter dated 16th August 1914 Frances responded to the news of Alfred’s enlistment with encouragement, but was clearly conflicted, adding

“that altho’ your going will hurt me as it will hurt Ruth, I wouldn’t say - don’t go… I honestly don’t believe I am afraid of dying – or death, tho’ I find it hardest to extend this feeling to the people I love.” iii

At this early stage of the war, Frances had already read about the events on the Continent in the newspaper, and was clearly opposed to the widespread enthusiasm and rush to join up, conscious of what it meant for the families involved

“Alfred I have had to read all the war news aloud to Mrs Bromley …. now I have to wade through all the awful details and they together with the Patriotic concert, have sickened me. I can’t help thinking of the feelings songs & martial music & bugle calls awake - contrasted with the grim awful details of the morning paper & of the millions of wrecked homes – to think that each of these soldiers has a mother, wife and sister, is loved as you are – perhaps.” iv

After enlisting he was sent to Broadmeadows Camp, located just outside of Melbourne. While there Derham was given duties as “orderly subaltern”v The waiting took its toll and he reported being in a “state of intense boredom.”vi

The 5th Battalion shipped out on the HMAT Orvieto (pictured) on 21 October and Derham was one of the 1,457 men and women on the ship, which represented a large portion of the Australian contribution to the war effort.vi The Orvieto arrived in Alexandria around 7 December 1914, described in detail by press correspondent Captain C.B.W. Bean.”viii

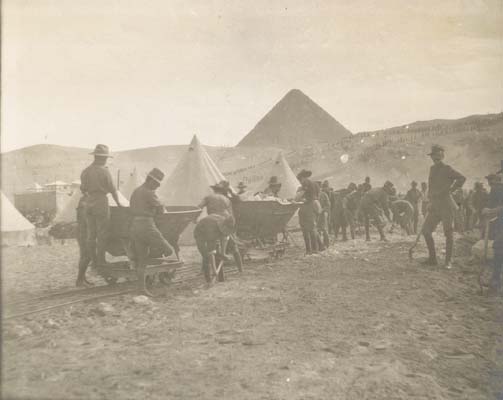

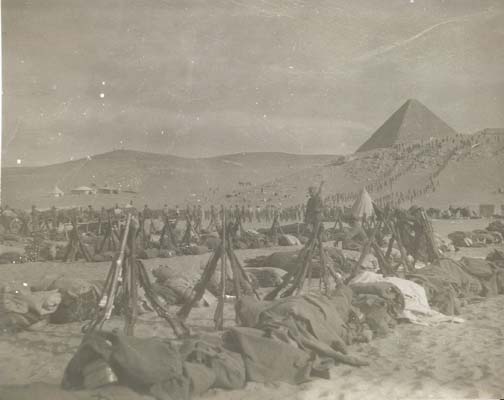

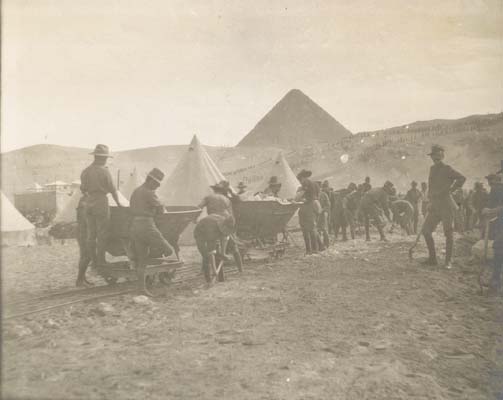

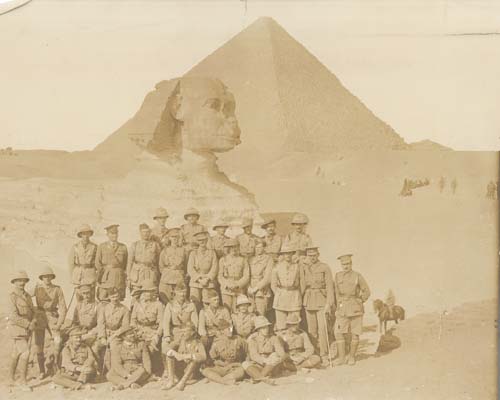

Bean also described the arrival of Australians at Mena Camp later that night in dramatic terms, emphasising the striking scene made by “Australians from Gumtree Flat and Dead Horse Gully ,from Murwillumbah and Sea Lake and Prahran and Surry Hills, camped right amid the tombs of the Pharaohs.”ix As was the case at Broadmeadows, waiting at Mena Camp made Derham uneasy, who commented that “life will drive us mad with monotony before we have been here many weeks.”x Several months after being deployed from Broadmeadows, Derham was clearly restless when he complained “we all shall be intensely disappointed if we return without going to the front or seeing service here.”xi On 5 April, the Battalion marched out of Mena Camp bound for Cairo Station “ten miles or more and quite trying on hard roads with extra heavy equipment”, and from there they took a train to Alexandriaxiv. After arriving in Alexandria, the 5th Battalion embarked on the HMAT Novian, a transatlantic cargo ship requisitioned for the war effort, bound for the island of Lemnosxiii. The 5th Battalion spent two weeks in Lemnos carrying out drills and practicing landing procedures before setting out for Gallipoli.

A.P. Derham’s time in Gallipoli was eventful and is recounted in memoir sent to Frances in late 1915. The memoir was written well after the fact, and is with a poetic detachment that often belies the danger and horrors witnessed at the landing at Gallipoli. Showing his naivety, Derham reflected that in the days leading up to the landing, while on manoeuvres around Lemnos, he recalled “see[ing] the snow capped hilltops of Samothrace and [?] and further to the right on the far horizon the dim land near Gallipoli, the land of our adventure.”xiv

On the 25 April, Lieutenant Derham and his platoon landed on the beach at the southern end of ANZAC Cove, and they soon took cover against nearby cliffs. With barely time to form up his men, Derham’s was ordered to place his platoon with ‘A’ Company and locate troops in need of reinforcement who had been separated in the confusion following the landing. Although Derham had been on active service since August 1914, the experience of the ‘front’ was something new to him. Derham later reflected that after the landing that “I myself had got over my nervousness at that time and had not yet begun to feel the fear which knowledge brings”xv, foreshadowing the terrifying realities of the battle to come.

The danger of the situation soon became apparent, in the form of heavy resistance from the Turkish defenders. Although a sense of danger is present in Derham’s diary, it is framed through distinctly poetic language.

“It was a beautiful day – we were out of danger from shrapnel behind a hill and the rifle and machine gun bullets were singing softly and harmlessly over our heads, sailing out with the summer sea like humming bees.”xvi

Other accounts of the landing at Gallipoli on 25 April paint quite a different picture. Private Ray Williams wrote in a letter home that “it was terrible to see the boat loads of lifeless boys that got mowed down without touching shore. The gunboats kept playing their big guns on the shore forts and batteries.”xvii Another wrote that “the Turks did not fire a shot till we were close in shore, then the whole place became a perfect hell with rifles, machine guns, artillery, and shrapnel bursting.”xviii

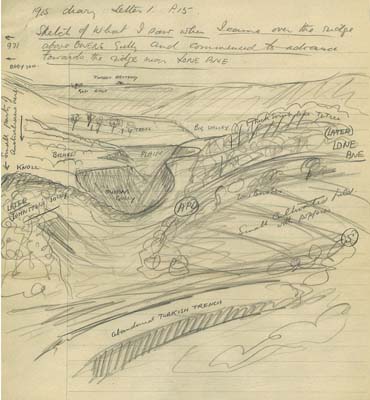

Lieutenant Derham commanded his platoon through the rough scrub and sloping terrain toward the area that came to be known as Lone Pine. He made a sketch of this landscape showing key strategic positions including a Turkish battery (pictured). In order to reach Lone Pine, Derham and his platoon crossed Monash Gully and Bridge’s River. When they arrived they met with Major Richard Saker another officer of the 5th Battalion xix, but there were “still no orders, still no firing line to reinforce, still nothing to do but lie and be fired at (badly thank heaven).”xx Rather than wait for further orders, Lieutenant Derham advanced his men in two short rushes in the direction of Owens Gullyxxi. During this movement he received word that Major Saker had been wounded. Derham returned to Lone Pine to assist the Major, but was hit through the left thigh by a Turkish bullet, “bringing me down like a sack of flour.”xxii Derham later recounted this incident in a dry, clinical manner.

“I found that my whole left leg was paralysed –probably from shock to the Great Sciatic nerve. I felt it very carefully and found it was not broken as I had at first suspected so I started to crawl towards where I had last seen Major Saker – doing this power gradually returned and I was soon able to hobble along slowly and unsteadily but not painfully.”

It seems that Derham was not able to reach Major Saker, who later died on the battlefield at Lone Pinexxiv. Although wounded, Derham refused to be transferred from battlefield until the 30 April, and his bravery and conduct during this time won him the military crossxxv. After recuperating from his injuries Derham resumed his service at the front, also serving in France in 1916, and returning to Australia to complete his medical studies at the University of Melbourne. During the journey back to the front in 1918, Armistice was declared.

Between the wars he worked in various medical positions around Victoria, was the director of the R.S.L. Children’s Health Bureau from its inception in 1933, as well as the Medical Officer of the City of Kew. In 1940 he left for Singapore as Assistant Director of the Medical Service, and spent time as a Prisoner of War in Changi with his eldest son Thomas during World War Two. The remarkable Alfred Plumley Derham Collection is listed and available on the UMA online catalogue http://go.unimelb.edu.au/fw9n

Frances became a key figure in arts education in Australia and was chairman of the A.I.F Women’s Auxiliary Prisoners of War Japan. Her extensive collection is also held at UMA http://go.unimelb.edu.au/fw9n

For more details on other collections containing World War One material refer to the subject guide available from the UMA website.