A single line in an archived letter sparked Faculty of Arts alumnus Andrew Anastasios’s fascination with the story that would ultimately become the movie The Water Diviner.

While conducting research on events at Gallipoli, archaeologist, writer and University of Melbourne Arts alumnus, Andrew Anastasios, discovered a line in a letter from Lieutenant-Colonel Cyril Hughes, a worker in the Imperial War Graves unit, who was recovering the dead after the war. The line in the letter, a footnote in a much more detailed account, simply said, “One old chap managed to get here from Australia, looking for his son’s grave.”

“Lt Col Hughes was trying to identify the bodies, and here was this father who just turned up from Australia, out of nowhere,” recalls Andrew. “It was a huge commitment and a serious undertaking to visit a country of which you have no knowledge.

“By that stage, the Ottoman Empire was being dismantled completely by the Allies, and so it was in disarray and the idea of just turning up in a country that is slowly being dismembered was really quite fascinating. I guess that line just jumped out at me.”

When Andrew approached (co-writer) Andrew Knight about his discovery, he too was excited to learn more. For up to a year, they researched in and around Gallipoli trying to identify the man and learn more about people who had similar experiences. Their search was fruitless.

Once they had concluded that they would be unable to find the real person, it gave them licence to construct a story for their intended screenplay. They were insistent, however, that if it was not going to be a true story, then it would at least be based on other people’s experiences.

A fresh perspective on Gallipoli

For all the focus on Gallipoli as the pinnacle of Australia’s participation in World War One, in creating The Water Diviner, Andrew Anastasios and Andrew Knight were eager to paint a more detailed picture of the Ottoman Empire at the time, to put the Gallipoli skirmish in the context of a much larger war. They wanted to show the consequences of what happened afterwards, during what was a deeply traumatic and transformative time for Turkey, and the fallout for the Ottoman Empire.

Dr Meaghan Anastasios, a writer, lecturer in the Faculty of Arts and “lapsed archaeologist”, as well as Andrew’s wife, worked with him on converting the screenplay into a novel. She credits their desire to tell this fresh perspective of the Gallipoli legend to being graduates of the University of Melbourne – where they had “innumerable fabulous teachers” who emphasised the importance of the bigger picture.

During the course of their research, investigating both the Australian and Turkish war experience, the writers explored Gallipoli and the major Turkish graves and memorial sites. They discovered diaries of Turkish soldiers and officers written on the front line.

“It’s not surprising, but we came to the conclusion that the experiences of the rank-and-file Turks was probably not that much different to the experiences of the rank-and-file Australians,” Andrew says.

“Which is why you have those days where the two camps of soldiers would meet, bury the dead, and after that, there was a real empathy and respect between them, which meant they never quite go at each other in the same way. They resumed fighting, but there was a grudging respect that had developed between them.”

On the subject of Turks as ‘the enemy’, Andrew is eager to highlight that they were defending their homeland, and that Australians had a more active role than is sometimes portrayed.

“When the Allies arrived in Turkey there was this sense that they would land on Gallipoli and would be in Constantinople within a couple of days. It was almost a fait accompli,” explains Andrew.

“But when the ANZACs met this massive resistance from the Turks, it was quite a shock, and the reports coming back to Australia were ‘Oh yes, minor setback but a couple more days and we’ll be okay’. The reality on the ground, however, was that it would develop into a stalemate. It was very important for us to demonstrate the opposite view in the film – the idea that the Turks were defending their country and we were invading it.”

The film has been described as ‘anti-war but not anti-warrior’, a balance which Andrew believes remains respectful to the ANZAC experience and to the individuals that fought. During the writing process, they were careful not to devalue the role that the Australian soldiers played and were mindful of the importance of the ANZAC legend and of the sacrifices that were made by the individuals and their families.

Responses to The Water Diviner

The response novel The Water Diviner, which was written after the screenplay, has been hugely rewarding for Meaghan and Andrew.

“To hear from people out there who have really enjoyed it and are engaged with it and thinking about it, just as I know how I feel when I see a film or read a book, that really moves me”, says Meaghan.

The couple are equally excited by the academic impact of their work and the conversations it is sparking.

“I don’t think at any point we held the view that it wouldn’t be controversial,” says Andrew. “There are elements that people like, and that people don’t like, and depending on what country you’re from, your political viewpoints or what your view of Gallipoli is, there are conversations to be had about what we have presented and our interpretation of the history. But it’s really rewarding to see those conversations taking place.”

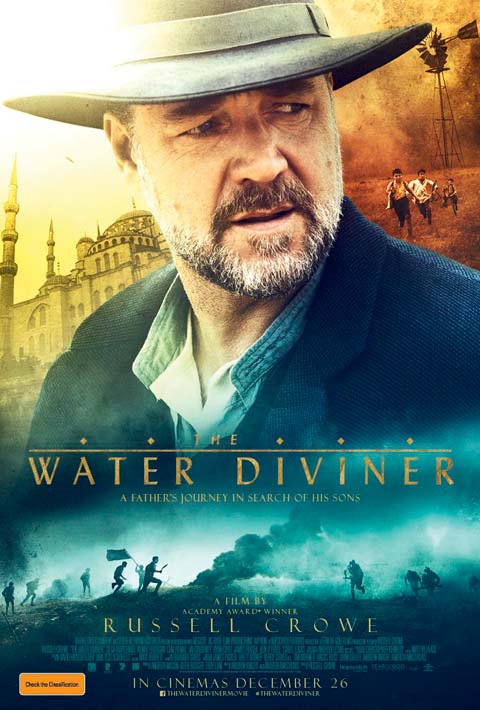

The movie, The Water Diviner, is now available on DVD. The novel is available from book stores across Australia. Bolinda has also published the novel as an audio book narrated by Jack Thompson. Faculty of Arts alumnus Andrew Anastasios (BA(Hons), MA) co-wrote the original screenplay for The Water Diviner, an historical drama directed by Russell Crowe. The script for The Water Diviner was adapted into a novel for Pan Macmillan by Andrew and his wife, Dr Meaghan Wilson-Anastasios (BA(Hons), MArtCur, PhD), who is also a Faculty of Arts alumna and lecturer at The University of Melbourne.

Read next: Alfred Plumley Derham